On the heels of THE SOCIAL NETWORK's 8 Oscar nominations this morning, we now return to our exploration of the filmography and protagonists of David Fincher. Part I can be found here.

ANGRY PERSON #4: NICHOLAS VAN ORTON (THE GAME)

Following the critical and commercial success of SE7EN, Fincher could have done almost anything he wanted. So why, in the whole wide world, did he pick a script from the writers of THE NET? (Amusing side note: these two All-Stars would go on to write TERMINATOR 3: RISE OF THE MACHINES, TERMINATOR: SALVATION, and Halle Berry's CATWOMAN. We can all dread Anne Hathaway stepping into Michelle Pfeiffer's boots if we want to, but I think we've already reached the depths of Catwoman-related depravity, don't you?)

Despite the astounding levels of future failure reached by these writers, THE GAME actually remains a very fun film, and a very Fincher-ian one at that. All three films I'll look at today hinge on an exploration of violence and subdued anger, and it's a definite thematic link through this section of Fincher's filmography. THE GAME does this almost entirely through the character of Nicholas Van Orton, one of Michael Douglas' most interesting performances.

The emotional key to his performance is the line, "Right now, I am extremely dangerous," which comes in the last act of the film. Fincher's interested in what leads him to this point. Van Orton is set up as an emotionally frigid and aloof character, but the film charts his path from disconnected loner to violent paranoid in such a way that, by the end of the film, Douglas seems more rabid animal than sophisticated man of finance.

Not to say this transformation isn't understandable. Van Orton is the audience's eyes and ears - every scene is told from his perspective. He is the one constant. He is us. THE GAME is a wonderfully post-modern film, playing with genre conventions in a dizzying, layered way, and if you can convince yourself that "the game" is really about filmmaking, there's an interesting angle to approach the character of Van Orton from, where he literally becomes the embodiment of a film audience.

At the beginning of the film, Van Orton is a man in charge of his environment. He lets nothing and no one in. All of his relationships are strictly one-way, similar to our notions of how the relation between film and viewer should be. But from the moment the game begins, Van Orton begins to surrender control, first over his environment, then over others, and finally over himself, to the point where he is willing to commit murder. He is driven to a point where his control ceases to exist, and he becomes pure rage.

It's relatively clear what Fincher is saying about humanity here, that we live in delusions of control, and underneath these pretenses is a simmering rage at being unable to reign in the chaos of life (sidebar: holy shit, was this what ALIEN3 was supposed to be about? Is the alien a representation of the rage at our own illusions? Did I not get enough sleep last night?), but what is he saying about film?

The key here is whether or not we believe Van Orton "completes" the game. Certainly, there seems to be an ending, and a lesson learned, but there's that ambiguous scene at the very end of the film which leaves this question open to interpretation. If Van Orton completes, then Fincher's thesis on film appears to be that the medium (and, I suppose, art as a whole) allows us to learn things about ourselves, but that it's ultimately an entertainment. If the game continues on past the credits, than the view of film is decidedly more complex, arguing that we may be unable to categorize between reality and fantasy, that they can become interchangeable, and that we live in both, perhaps simultaneously.

ANGRY PERSON #5: TYLER DURDEN/JACK (FIGHT CLUB)

Which brings us to living two realities at once, and the inherent envies and wraths that entails. Have you, somehow, not seen FIGHT CLUB? Because not only should you not read the next section, you should also run out to your local place of video procurement, get a copy, and watch it at your earliest convenience.

Actually, there's not a lot I want to talk about in regards to FIGHT CLUB. The whole film seethes with rage at the trappings of modern society, perfectly given a voice in Tyler Durden, who sounds like some sort of Oprah-Unabomber love-child:

Tyler: Man, I see in fight club the strongest and smartest men who've ever lived. I see all this potential, and I see squandering. God damn it, an entire generation pumping gas, waiting tables; slaves with white collars. Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don't need. We're the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War's a spiritual war... our Great Depression is our lives. We've all been raised on television to believe that one day we'd all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars. But we won't. And we're slowly learning that fact. And we're very, very pissed off.

Brad Pitt's Tyler Durden is essentially the other side of David Mills, his detective character from SE7EN. The depiction of anger in SE7EN was about how that emotion blinded and enslaved us. FIGHT CLUB is about that, too, but it approaches it from the completely opposite angle - from a look at how that anger feels freeing and exuberant. Tyler Durden is a man without limits, freed by his rage to accomplish anything. Of course, that's because he's only half a man. Here, Fincher finally gets down to why anger is such a powerful force: because it feels good. We give into anger because the anger feels like it completes us, or brings us power.

The flip side of the coin is Ed Norton's character, who has no name, but is usually referred to as Jack (due to the meme-inspiring "I am Jack's colon" articles the narrator reads aloud at one point). Jack is consumed with jealousy, and it is this jealousy that helps make him relatable. Durden's anger gives him power, but it also makes him an outcast. It's through Jack's envy of Durden's freedom that we enter the world of FIGHT CLUB. It's a perfect mirror to the interior conflicts of the social contract. Our surrender of the survival instincts in exchange for the comforts of civilization chafes against the animal inside each of us. On some level, we envy the purity of the animal kingdom. Despite our intellectual understanding of the benefits of society, a part of us emotionally wants to be an alpha male, or a mother protecting her cub, because it is, in a word, simpler.

ANGRY PERSON #6: MEG ALTMAN (PANIC ROOM)

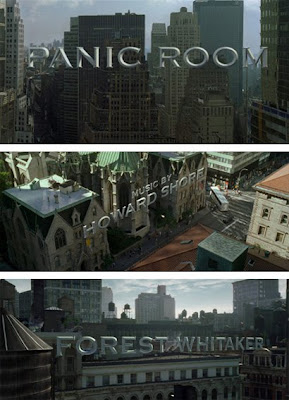

That simple mother-cub relationship is at the crux of PANIC ROOM. But first, before we get too into this, can anyone explain these fucking titles to me?

This is the first time I can remember seeing these 3D titles composited into live plates like they were actually hanging in real space, and even then, I was confused. What are they supposed to represent? Are you making me aware of the artifice of the titles for any particular reason? I'm pretty sure it's just supposed to look cool.

And that's pretty much the reason I think PANIC ROOM is kind of a shitty film (along with this ridiculous look-at-me into-the-lock-through-the-coffeepot-handle establishing shot, which no one will be able to convince me was a good idea). It's a film obsessed with style, and little else. There's some suspenseful moments, but it's not a film you ever really want to re-watch. Fincher ushered in the era of the completely-previsualized studio film with PANIC ROOM, diagramming the entire set in a computer and moving around little digitized models of his actors so he could work everything out before shooting commenced. When Nicole Kidman dropped out of the production, and Jodie Foster stepped in, all the camera information had to be re-calculated for the 8" difference in heights between the two actresses. The whole thing is just a little too constructed.

To that point, I've read defenses of PANIC ROOM that argue that the entire film is constructed as an elaborate look at Freudian psychology, with either the different levels of the house or the three thieves representing the id, ego, and superego. I'm not sure that I buy that (in fact, I'm pretty sure I don't), but there's definitely a tug-of-war between those animalistic tendencies and the higher forms of social behaviour throughout the film.

Meg tries to bargain with the thieves at first, negotiating with them, but it devolves into a fight for survival fairly rapidly. This is another reason PANIC ROOM is less interesting than Fincher's other films from this period. THE GAME and FIGHT CLUB are about a struggle between ideologies. PANIC ROOM is like a time-traveling Roman emperor who microwaves some popcorn, throws a sledgehammer and a gun into the Colosseum, and gives Jodie Foster a shield, just to sit back and see what happens. I mean, it's still interesting, and other films have been made about pretty much this exact thing (subtle Ridley Scott burn!), but it doesn't really engage the viewer mentally beyond a where-are-they/where-is-she interest. PANIC ROOM is all about visceral, primal needs.

I think that's been enough for one day. I'll be back with an evisceration of Benjamin Button and Jake Gyllenhaal, then balance it out with praise for Jesse Eisenberg and why I think Fincher really, really needs to not do the remake of THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATTOO.

The emotional key to his performance is the line, "Right now, I am extremely dangerous," which comes in the last act of the film. Fincher's interested in what leads him to this point. Van Orton is set up as an emotionally frigid and aloof character, but the film charts his path from disconnected loner to violent paranoid in such a way that, by the end of the film, Douglas seems more rabid animal than sophisticated man of finance.

Not to say this transformation isn't understandable. Van Orton is the audience's eyes and ears - every scene is told from his perspective. He is the one constant. He is us. THE GAME is a wonderfully post-modern film, playing with genre conventions in a dizzying, layered way, and if you can convince yourself that "the game" is really about filmmaking, there's an interesting angle to approach the character of Van Orton from, where he literally becomes the embodiment of a film audience.

At the beginning of the film, Van Orton is a man in charge of his environment. He lets nothing and no one in. All of his relationships are strictly one-way, similar to our notions of how the relation between film and viewer should be. But from the moment the game begins, Van Orton begins to surrender control, first over his environment, then over others, and finally over himself, to the point where he is willing to commit murder. He is driven to a point where his control ceases to exist, and he becomes pure rage.

It's relatively clear what Fincher is saying about humanity here, that we live in delusions of control, and underneath these pretenses is a simmering rage at being unable to reign in the chaos of life (sidebar: holy shit, was this what ALIEN3 was supposed to be about? Is the alien a representation of the rage at our own illusions? Did I not get enough sleep last night?), but what is he saying about film?

The key here is whether or not we believe Van Orton "completes" the game. Certainly, there seems to be an ending, and a lesson learned, but there's that ambiguous scene at the very end of the film which leaves this question open to interpretation. If Van Orton completes, then Fincher's thesis on film appears to be that the medium (and, I suppose, art as a whole) allows us to learn things about ourselves, but that it's ultimately an entertainment. If the game continues on past the credits, than the view of film is decidedly more complex, arguing that we may be unable to categorize between reality and fantasy, that they can become interchangeable, and that we live in both, perhaps simultaneously.

ANGRY PERSON #5: TYLER DURDEN/JACK (FIGHT CLUB)

Which brings us to living two realities at once, and the inherent envies and wraths that entails. Have you, somehow, not seen FIGHT CLUB? Because not only should you not read the next section, you should also run out to your local place of video procurement, get a copy, and watch it at your earliest convenience.

Actually, there's not a lot I want to talk about in regards to FIGHT CLUB. The whole film seethes with rage at the trappings of modern society, perfectly given a voice in Tyler Durden, who sounds like some sort of Oprah-Unabomber love-child:

Tyler: Man, I see in fight club the strongest and smartest men who've ever lived. I see all this potential, and I see squandering. God damn it, an entire generation pumping gas, waiting tables; slaves with white collars. Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don't need. We're the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War's a spiritual war... our Great Depression is our lives. We've all been raised on television to believe that one day we'd all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars. But we won't. And we're slowly learning that fact. And we're very, very pissed off.

Brad Pitt's Tyler Durden is essentially the other side of David Mills, his detective character from SE7EN. The depiction of anger in SE7EN was about how that emotion blinded and enslaved us. FIGHT CLUB is about that, too, but it approaches it from the completely opposite angle - from a look at how that anger feels freeing and exuberant. Tyler Durden is a man without limits, freed by his rage to accomplish anything. Of course, that's because he's only half a man. Here, Fincher finally gets down to why anger is such a powerful force: because it feels good. We give into anger because the anger feels like it completes us, or brings us power.

The flip side of the coin is Ed Norton's character, who has no name, but is usually referred to as Jack (due to the meme-inspiring "I am Jack's colon" articles the narrator reads aloud at one point). Jack is consumed with jealousy, and it is this jealousy that helps make him relatable. Durden's anger gives him power, but it also makes him an outcast. It's through Jack's envy of Durden's freedom that we enter the world of FIGHT CLUB. It's a perfect mirror to the interior conflicts of the social contract. Our surrender of the survival instincts in exchange for the comforts of civilization chafes against the animal inside each of us. On some level, we envy the purity of the animal kingdom. Despite our intellectual understanding of the benefits of society, a part of us emotionally wants to be an alpha male, or a mother protecting her cub, because it is, in a word, simpler.

ANGRY PERSON #6: MEG ALTMAN (PANIC ROOM)

That simple mother-cub relationship is at the crux of PANIC ROOM. But first, before we get too into this, can anyone explain these fucking titles to me?

This is the first time I can remember seeing these 3D titles composited into live plates like they were actually hanging in real space, and even then, I was confused. What are they supposed to represent? Are you making me aware of the artifice of the titles for any particular reason? I'm pretty sure it's just supposed to look cool.

And that's pretty much the reason I think PANIC ROOM is kind of a shitty film (along with this ridiculous look-at-me into-the-lock-through-the-coffeepot-handle establishing shot, which no one will be able to convince me was a good idea). It's a film obsessed with style, and little else. There's some suspenseful moments, but it's not a film you ever really want to re-watch. Fincher ushered in the era of the completely-previsualized studio film with PANIC ROOM, diagramming the entire set in a computer and moving around little digitized models of his actors so he could work everything out before shooting commenced. When Nicole Kidman dropped out of the production, and Jodie Foster stepped in, all the camera information had to be re-calculated for the 8" difference in heights between the two actresses. The whole thing is just a little too constructed.

To that point, I've read defenses of PANIC ROOM that argue that the entire film is constructed as an elaborate look at Freudian psychology, with either the different levels of the house or the three thieves representing the id, ego, and superego. I'm not sure that I buy that (in fact, I'm pretty sure I don't), but there's definitely a tug-of-war between those animalistic tendencies and the higher forms of social behaviour throughout the film.

Meg tries to bargain with the thieves at first, negotiating with them, but it devolves into a fight for survival fairly rapidly. This is another reason PANIC ROOM is less interesting than Fincher's other films from this period. THE GAME and FIGHT CLUB are about a struggle between ideologies. PANIC ROOM is like a time-traveling Roman emperor who microwaves some popcorn, throws a sledgehammer and a gun into the Colosseum, and gives Jodie Foster a shield, just to sit back and see what happens. I mean, it's still interesting, and other films have been made about pretty much this exact thing (subtle Ridley Scott burn!), but it doesn't really engage the viewer mentally beyond a where-are-they/where-is-she interest. PANIC ROOM is all about visceral, primal needs.

I think that's been enough for one day. I'll be back with an evisceration of Benjamin Button and Jake Gyllenhaal, then balance it out with praise for Jesse Eisenberg and why I think Fincher really, really needs to not do the remake of THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATTOO.

Brandon.

ReplyDeleteYou failed to mention how hot Deborah Kara Unger was in the Game. Please write a 1000 word essay about how hot she is in this movie and Crash.

Sincerely,

Deborah Kara Unger fan.

good lord Brandon, your blog is great but i can never get past the 2nd paragraph without getting a piercing blinding headache! cruel white on black and the tiniest of fonts! some of us are old and decrepit, have mercy! love your secret admirer hilary dean

ReplyDeleteBut black-on-white is so ... legible! Thanks, Hil, hope the headaches cease.

ReplyDeleteAnd Wytze, I wrote some pretty good DKU slash-fiction in my youth. If you scour the internet *ahem* hard enough, I'm sure you'll find it.

Wow, you're amazing, that's really nice of you. i feel kind of bad for ruining everything though. maybe you should take a vote and if i am the only old lady complainer, i will concede.

ReplyDeleteI like it. It's like the desert.

ReplyDelete